This article was originally published on April, 2020 on NFX Blog and was writing by Gigi Levy – Weiss. Gigi is a Managing Partner at NFX, a seed-stage venture firm based in San – Francisco.

Speed is your one advantage as a startup. During a market downturn, this is even more true. While your competitors can become slow or fearful when markets drop, downturns open a clear pathway for you to gain ground and come out stronger. But this requires upping your game — and one of the critical ways to do so is to become a faster learner.

There’s an underlying mechanism in iconic startups that often goes unseen: they are learning machines, constantly improving themselves to deliver better results.

Beneath each function in a successful startup are a series of feedback loops and a team of learners. I saw this in each startup I co-founded, including Playtika, which was acquired for 16₪ ($4.4) billion. My first encounter with a learning organization, however, was when I joined the Israeli Air Force.

The Israeli Air Force has some of the best pilots in the world, yet they put a low amount of hours into training. This is the impact of building a rigorous methodological learning system into each individual and unit.

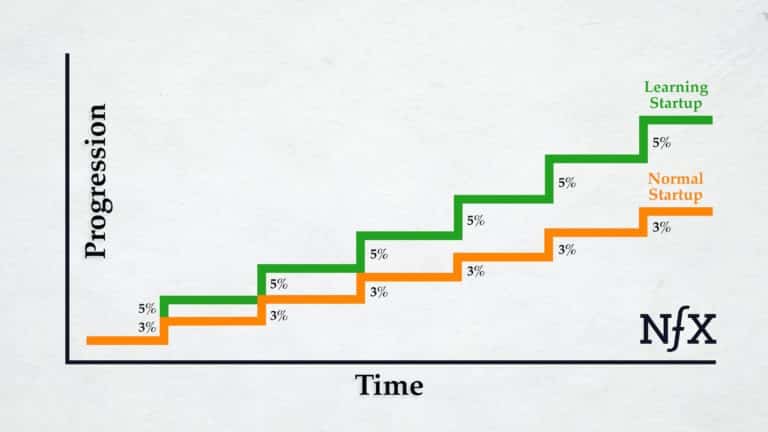

In the Air Force, you must improve between flights or missions. In startups, you need to improve between your iterations — but the principles are exactly the same. The mathematical effect of getting this right justifies the time Founders should be spending on it. Assume that in every iteration a learning organization gets 10% better than a non-learning one. The compounding effect post 10 iterations makes it 2.5x faster than the non-learning competitor.

To implement learning loops correctly, there are 3 important and highly nuanced components.

First, a learning culture is built upon a series of company-wide rituals and rules.

Many startups have “retrospectives” after an important project — if you don’t already have this, you should. But it’s not enough. What you need is a culture of debriefing every iteration.

To be clear, this isn’t about having meetings for the sake of meetings. It’s about quickly and efficiently reviewing work, comparing it to the goals and assumptions, analyzing the outcome, and becoming better. Here you can see the methodology and culture which is created:

1. Every performance is debriefed

In the Air Force, you have to stand up in front of everyone and debrief your performance after every flight. You learn to say “These were my mistakes and this is how I am going to improve them.” This may sound like a strict guideline that should be followed for only the most important missions, but this methodology must be implemented for everything. A training mission should be debriefed like an important operational flight. This culture — and make no mistake, this is an element of company culture, requires that a minor driving issue like backing into a tree in a car must be debriefed and analyzed like an issue during a flight mission. In a startup, the principle is the same — how you do one thing is how you do everything and the highest leverage learnings are not always derivative of the “important” things. True learning requires consistency.

2. There are no perfect performances

The worst thing you can do in a debrief is say that everything was perfect. That means that you are either blind to your own mistakes or not transparent and afraid to share them. Even if your performance was great and your mistakes small, you must find them and share them openly. This is the way to force yourself to learn and improve, to show everyone you are a learning person, and set the example for everyone else in the organization.

3. Every debrief informs the next iteration

Once you finish analyzing what you’ve done, compare it with the goals you had set and find out what you’ve done well, and what you didn’t achieve. Then determine which of those goals carry into your next mission, so one debrief feeds the next iteration. Startup learning is the same — the learning from each iteration becomes the baseline for the next. This may sound like something that everybody would normally do, but it’s incredibly difficult to implement because it requires a rigor that only the very best tend to have.

Second, transparency must be seen as an organizational imperative.

If you’ve made a mistake, the worst thing for your company is to not share it openly. Not only is it bad for the organization, but you’re blocking your own learning. If you’re in denial about what went wrong or aware of what went wrong but don’t share it, you’re preventing your ability to improve, and the ability of your organization. The key is transparency. Without it, no one can learn and improve, in the Air Force or in business.

1. Share the reality

In one company I worked for, we lost a large tender with an important customer. Other than the tender team, no one knew why. Some people on the team thought we should say that the other participant’s offer was cheaper. It was the easiest way to not get reprimanded. We didn’t know exactly why we lost, but we received feedback that our offer wasn’t well prepared. If I had played along with this, we wouldn’t have changed the way that the company answered tenders. We ended up sharing the reality across the company and did a deep review of the way we answered tenders, which led us to win many others. This transparency was not easy for the team in the short term, but it was good for everyone in the long run. This is one small example of how openly sharing the truth drives cross-company improvement.

2. Embed it in your culture

Building your culture is critical for your success as we wrote before, and transparency is a core part of any successful startup’s culture. Make sure it is part of yours. To make it visible every day, I used to ask my team, “What didn’t work for you last week? What are you going to do about it and how can I help?” It can be that simple. My asking this led them to ask the same of their teams and it became the language of the organization.

3. Make it seen

Use company-wide events, newsletters, and podcasts to emphasize the importance of being transparent and the learnings that come from it. Actively show your employees that you are happy with them sharing their mistakes and are open to sharing yours. People have to see this with their own eyes and you have to lead by example. Some CEOs feel this could make them look weak, but the reality couldn’t be further. Your team probably knows a lot more than you think about what happened and will appreciate your openness and transparency, and in turn, will behave the same.

4. Non-learners not welcome

Identify the people who are not learning and not making their mistakes visible. Make it clear that this is not acceptable. Each person who is not sharing is slowing the company down and the effect of multiple people like this is compounding. On the other hand, those who share their mistakes and learnings openly are force multipliers beyond their actual job skills. These are the people you want on your team.

Third, scrutinize your wins as much as your losses.

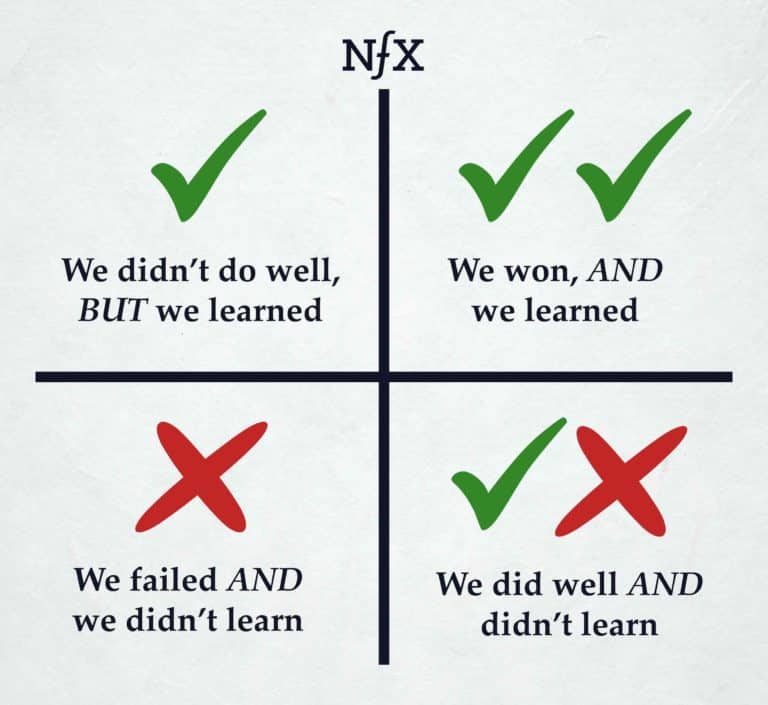

You can bring in a 18₪ ($5) million deal and help build your company, but in the process, you might have sent out the wrong proposal and had to recover. Tons of things can go wrong, and you can still win. Most organizations focus on the win and miss out on the learning that can accompany it by doing a debrief. The secret is to associate learning not just with failure but also with success.

1. Learning as you win

If you go to a trade show and everything worked and you walked away with 79 leads, everybody is happy, right? But if nobody stops and says “You know, that was good, but what could have made it better? Where did we make mistakes?” you’re missing out on an opportunity to learn and improve. The reality is that you can be really successful, and still learn along the way.

The worst quadrant in the chart below is “We failed AND we didn’t learn.” You never want to be there. But “We did well and didn’t learn” is only slightly better. “We didn’t do well, but we learned,” is good because hopefully what we learned will win us the next 10 deals and not just one. The best is “We won, and we learned.” That’s where you want to be. You want to be winners who are learning and improving as you win.

2. Being in learning mode is a Founder superpower

When I ran a gaming company, whenever we had a promotion campaign we would debrief afterward with full analytical research. It would always include a comparison of how the promo did compared to how we projected it would do. Many of our biggest learnings came from our overperforming promotions. By forcing ourselves to question why we thought it would deliver less than it actually did, we once found a crazy link with the weather. The promotion occurred over a stormy weekend, and people ended up staying home and playing more games. This gave us a totally different way to think about promotions based on the weather. If we’d just celebrated our win without questioning it, we would have missed that. Always being in learning mode is a superpower you want to develop.

3. Celebrate good failures as “mini wins”

As a Founder CEO, I also used to hold “failure celebrations.” Whenever we had what I deemed a “good failure” — one where you worked hard, based your decisions on data as much as possible, and eventually failed for product-market fit reasons (and not due to poor execution or politics) — we would have an event that was almost the same as if celebrating a success. The team would stand in front of everyone and provide an analysis of what didn’t work and why. This ensured the organization kept learning and improving without employees openly fearing debriefing, learning, and teaching others how to be better.

A Mathematical Advantage

Since most early-stage startups fail, survival and success is often about doing everything possible to improve your odds. Because startups work in iterations, the biggest question you can ask yourself is how can you make sure that your organization and team is a learning one and your next iteration is going to be better than the previous one.

The only way to guarantee it is going to do better is to implement learning and feedback loops. If you don’t do that, every iteration starts at the same place that the previous one ended. If you’re a learning organization, your next iteration has a better chance of succeeding. Over time this will give you and your startup a dramatically higher chance of winning.